So your long-awaited holidays in southern Italy are over, you just travelled from 28°C sunny to 13°C solid grey in less than three hours and timely caught the Italian disease while waiting for your lift outside Amsterdam Airport. They call it il colpo di freddo, “the hit of cold”; its symptoms include chills, slightly sore throat, a mild cough or sneezing, headache, running nose, stiff neck and general asthenia. It may associate with grumpiness.

There’s only one thing left for you to do: go home as fast as you can and make soup!

First of all, I don’t want you to panic about colpo di freddo: if you’re not Italian, you might be immune by birth; if you are, you know better than I do that there is no cure, so just enjoy life till it lasts.

I don’t want you to think I’m whining about the Dutch weather either, as I’m not of the complaining type and there is nothing more pointless than making a fuss over something you can’t change in any way (I know you can sense a “however” coming up, and you are not mistaken)… However, my body demanded some comfort food for brutally being shovelled into winter clothes after two weeks spent half-naked in the sun, feasting on sun-grown food (any repetition of the word ‘sun’ is patently and painfully intentional).

I got home and delved into my pantry even before unpacking. I found a souvenir from a trip to Torino, northern Italy.

When in Torino, I never miss a visit to Porta Palazzo, the largest street market in Europe.

A grocery store facing the market, called Ditta Ceni, holds a special place on my shopping list. Tens of varieties of legumes are displayed in gunnysacks lined up in their shop window and sold by weight.

If you mostly shop at supermarkets, you may tend to forget that beans and peas come in tens of thousands of different types, shapes and flavours. Over the centuries the food industry has selected the most profitable cultivars and this is why our choice is normally limited to 3-4 bean types when browsing the isles of the average supermarket.

Other varieties are often endangered, because no longer marketable.

Luckily, organisations like Slow Food International encourage and support the preservation of traditional and local foods against the impoverishment of food biodiversity inevitably brought on by food mass-production.

I am fond of the people who spend their lives reminding us that profit does not always coincide with worth, an important truth we tend to overlook.

Ditta Ceni, the small shop on Porta Palazzo market, sells many Slow Food Presidia – the products Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity strives to protect from extinction -, so last time I was there I bought some oddly looking peas without even knowing what to do with them.

All I knew was that their unusual name: roveja.

There they were, in a paper bag that had been sitting in my pantry for a long time. The seeds were round and corrugated, with colours ranging from greyish brown to dark red; good material for a hippy necklace, but how do you cook them?

I got a sudden intuition. I guess motivation is key: I needed a reminder that winter can be likeable, a reminder in the form of a tasty rustic soup.

I did my research about roveja and found out that it is a very ancient wild pea, originally from Western Asia. It had been cultivated in Central Italy for centuries when its commercial decline began, with the introduction of mechanical harvesting.

The long stalks of roveja plants make it impossible for threshing machines to harvest them: to this day the crops are scythed manually and only a few producers are still in business in the Italian regions of Umbria and Marche.

This field pea is high in proteins and makes a good source of potassium and phosphor. Besides nutritional facts, I found out that roveja is really tasty: its flavour stands somewhere in between broad beans and lentils.

If you are going to travel in central Italy anytime soon, I invite you to buy some to support the producers and give it a try.

After soaking the roveja overnight and boiling it, I explored its texture and taste to figure out what flavours would match it best.

I decided to combine it with another Italian winter food, pizzoccheri, a buckwheat flat ribbon pasta typical of Valtellina, a valley in Lombardy, northern Italy.

Pizzoccheri – also a traditional food, dating back to the XVI century – are definitely easier to source outside of Italy than roveja. You should be able to find their dry version in some supermarkets or specialist delis. If not, you may be brave enough to try making it fresh on your own. If you have some experience making pasta, it shouldn’t be too difficult; the proportions are 2/3 buckwheat and 1/3 wheat flour.

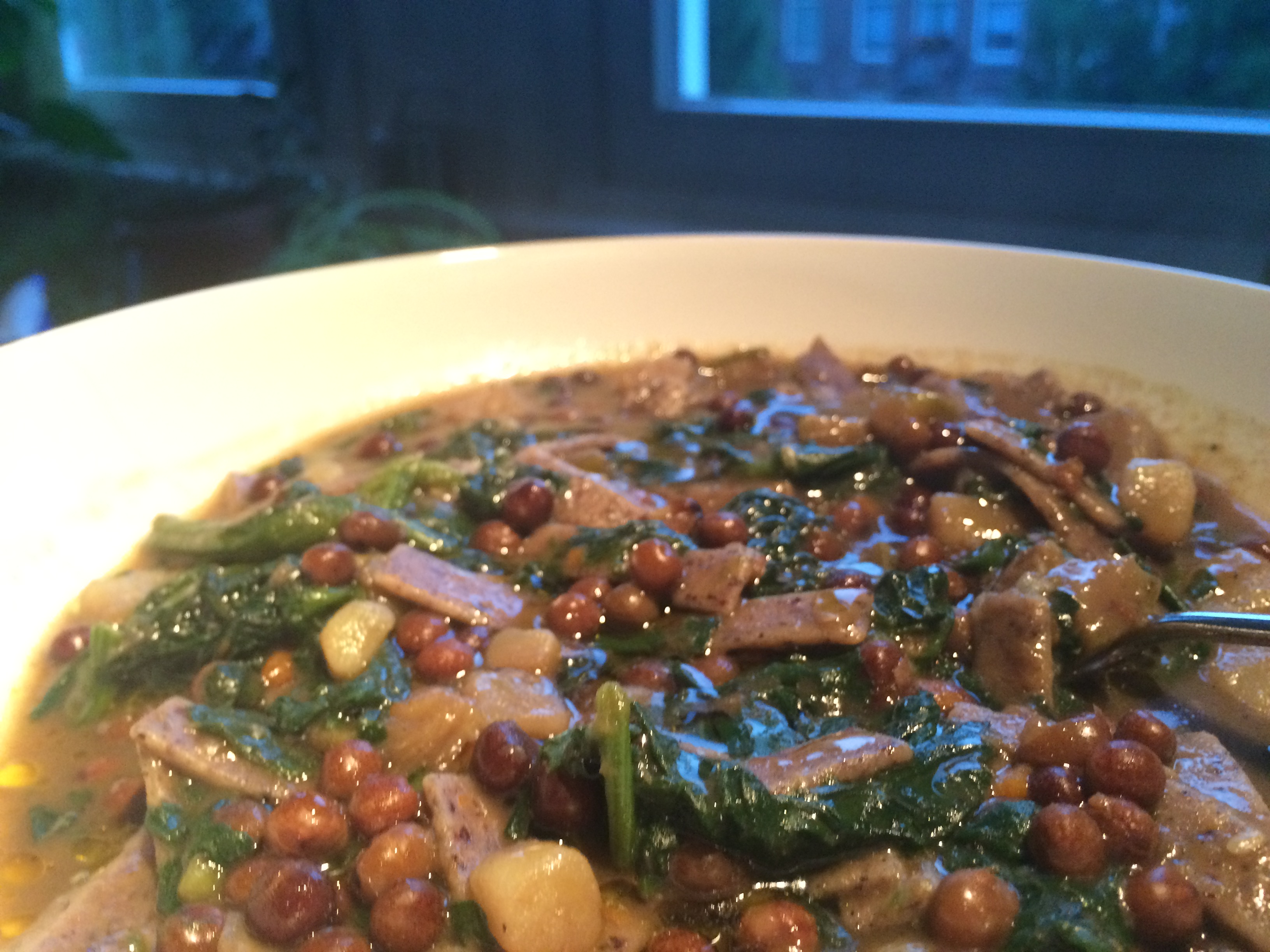

To my personal taste, the nutty winter flavour of pizzoccheri combines very well with that of roveja.

As an alternative to roveja, if you really can’t get hold of it, I suggest that you use some local variety of slightly bitter field peas and let us know what you used – feel free to use the comments section to share your experience. To those who live in the Netherlands I would say that the closest substitute for roveja could be Dutch kapucijners.

Here is the recipe I came up with.`

Ingredients (serves 3 hungry people):

– ca 250 g roveja (dry)

– 1 medium-sized courgette

– 1 fairly sized carrot

– 1 big potato

– 2 medium-sized shallots

– 1 garlic clove

– 120 g dry pizzoccheri

– 300 g spinach

– nutmeg, salt, extra virgin olive oil

I soaked the roveja for 24, but 12 hours should be enough.

After accurately rinsing the legumes (and using the soaking water to water my plants), I put them in fresh water with a strip of dry kombu seaweed and brought them to a boil, then kept them to a gentle simmer for 45 minutes, until they were cooked but still keeping their shape. I’ve used kombu to cook legumes for years, since I found out that this seaweed makes them more digestible and adds minerals to their broth. I normally discard it before moving to the next phase of the preparation.

I heated the olive oil in a cooking pan with the garlic clove (smashed or cut in halves, depending on your own preference), let it go for a minute, then added the shallots, finely minced.

The fire should never be too high: you want the shallot to sauté without burning.

When the shallot had shrank, I added diced potato and carrot. I like carrots to be cut in very fine pieces in soups – sometime I even get to grind them – but again, this is up to your personal taste.

I stirred for some minutes and lastly added the diced courgette, then the roveja and poured in enough of its own broth to cover the ingredients by 2-3 cm. I also added some granular vegetable bouillon, but if you have the time to make your own bouillon, that’s even better; you can mix it with the broth from the roveja.

I let the pot simmer for about 30 minutes, or until the potatoes were soft but not breaking down.

At this point I added more broth/bouillon and brought it to a stronger boil, then added salt before the pizzoccheri.

These latter cook for about 12-15 minutes. They should be firmer than the usual tagliatelle.

Half-way into the cooking of the pasta, I added the spinach. This was actually a leftover from my previous meal. I had served it as a side dish but thought it would match the soup deliciously, which it did.

This is how I had cooked the spinach: I put a sliced garlic clove in a frying pan where I had heated 3 spoons of extra virgin olive oil. I added the spinach and covered the pan for a few minutes, just until the spinach had shrank, then let it cook and stirred a few times, and finally added salt and nutmeg when the spinach was almost cooked.

Once I added the spinach to the mix, I let the soup cook until the pizzoccheri were done and finally served it with some extra uncooked olive oil.

A variation of this soup can be made with cavolo nero in place of spinach. This will make the taste much more rustic, whereas the spinach version is sweeter.

I was very happy with the result, but I am afraid I will need more soup to put up with this early winter!

Da provare al più presto!

Tu che puoi reperire facilmente gli ingredienti non ti puoi esimere!