I received my first birthday present up in the sky this year.

The author of the gift was my dear friend Nina, with whom I was travelling from Amsterdam to Lucca, Italy, to celebrate.

We were probably flying over Germany or France when she handed me a funny patterned bag and wished me happy birthday.

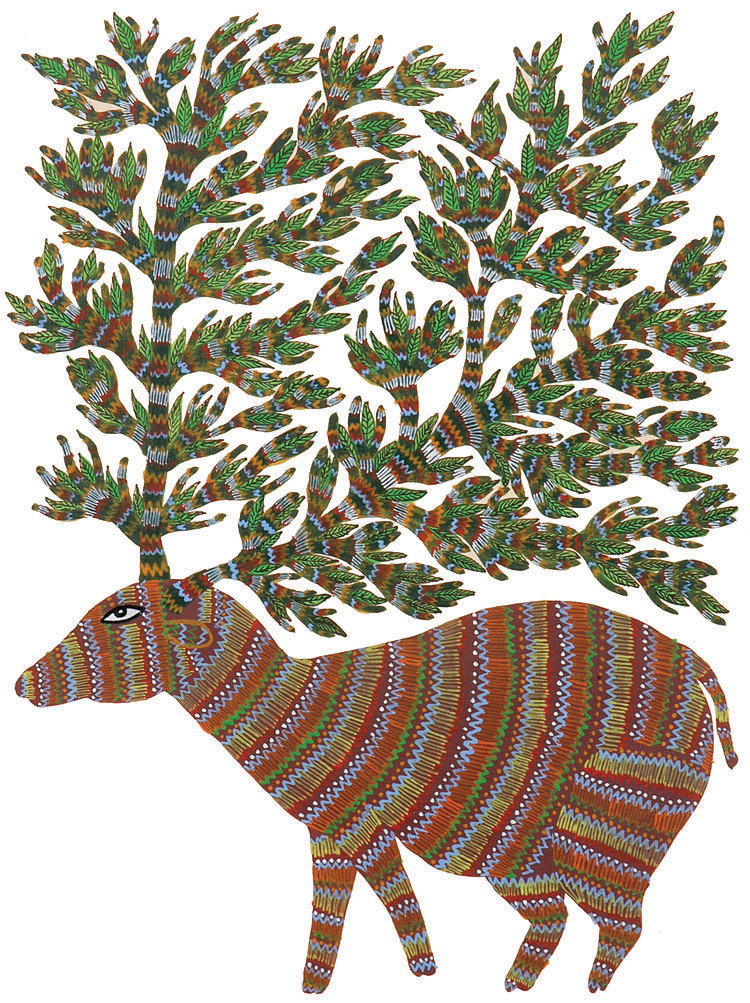

The bag revealed a large hardcover illustrated book entitled The London Jungle Book. I had never seen it or heard of it or its author before, and its quirky artwork looked quite unfamiliar to me.

Nina seemed to read my mind and kindly added some background: she had bought the book on her latest visit to southern India, where she is from; it was the travel journal of a young Gond artist who saw London for the first time and the illustrations were in Gond style.

Ehm, …right. Of course: Gond, that tells it all! How could I miss that?

I have never set foot outside of Europe and although I like to consider myself a cosmopolitan citizen of the world, my passport lies hopelessly underused in my nightstand drawer, blank like my mind while trying to figure out an adequate metaphor for its blankness.

There was a time in my youth when I used to daydream about exploring the world on my own, by “world” meaning the unknown, the wild, the different and the distant.

When not travelling solo, I would have been with Fiammetta, my best friend since the age of 14, with her pocketknife named Jonathan to protect us (this was her thrilling contribution to that fantasy).

I soon had to realize how delusional I was, what a quest even getting out of my hometown to see some Europe would turn out to be, and how awfully little is my knowledge of the world to this day.

So I had never heard of Gond art, but I loved the gift even before understanding it; its mystery having me like it even more, in fact.

I didn’t ask more questions, as I have always enjoyed reading too much to believe in prefaces of any kind. I am the type of reader that keeps introductions for last, if she ever reads them; guided tours are not my cup of tea.

Only many Tuscan trattorias, parks and churches later – back on my crooked couch in Amsterdam – was I to find out about the Gonds, a tribal people living in the forests of central India, who were studied by English anthropologists such as Verrier Elwin back in the 1930s. This adventurous guy married a 13-year-old Gond girl and considered his reports about the Gonds to be comparable to Kipling’s Jungle book.

Less experienced of the world than the early ethnologists who had mingled with his people, the Gond artist Bhajju Shyam had barely left the village of Patangarh in his whole life when he was appointed to decorate the walls of an Indian restaurant in metropolitan London.

In a mixed emotional state of excitement and fear of the unknown, he set off to a journey that he lived and described as a true adventure of its own kind.

The first time I set foot in London it was with my best friend; it was also the first time I ever travelled on my own, the first time I took a flight, the first time I spent my own money (I had cashed a bond that my grand-grandfather had put in my name when I was born), the first time I would ever have to rely on my English to speak to someone, and the list goes on.

I was eighteen and my friend would turn the same age a few days into that epic, long fancied holiday. She was still affected by that crazy knife thing, by the way: Jonathan was discreetly travelling with us (thank goodness she grew out of the knife fixation eventually).

Even in my complete naivety, as a born and raised European teenager, I kind of knew what to expect from London. I had been taught how to read it in many ways. My interpreters were the mild stereotypes about Britons I had somehow assimilated over the years (tea with the queen, bobbies, Brit pop, unlikely hats…), my Routard guidebook, my English books from school – one of which, I remember to this day, opened a chapter with the statement “London is a cosmopolitan city”. To my recollection, that’s how I first came across the concept of cosmopolitanism, and I think this also contributed to frame my experience of London before even getting there.

Five years later, in 2004, Bhajju Shyam saw a different, unprecedented London. One would assume that, as someone from an ex British colony, he would bear some preconception of what London would be like. If he did, it doesn’t show at all.

In fact, as a young artist coming from a small and marginal village in tribal India, not even speaking English, he had no prior knowledge of the city nor any easy access to its meanings.

Under his unbiased look, each step into that journey turned out to be an undiscovered mystery, to receive and explore as though crossing a virgin jungle. Every detail that would seem trivial to anyone who had seen London or Great Britain even only on TV or read about it – the tube, pub-goers and workaholics, the City, ethnic restaurants and double-deckers, punks, multitasking powerful women, umbrellas popping open in the pouring rain (very strange) – would find Shyam in utter amazement.

Once he got back to his hometown, after two months, he could not speak of anything but London, and people would come to eagerly listen to his stories.

He suddenly had drawn the kind of attention that is privilege of the storyteller, as if travelling had made him automatically elder, wiser, a living theatre of otherwise inaccessible stories and characters: he had become, in his words, The Bard of Travel.

One year later, his stories and the freshness of his view of the city were as vivid and insightful when he met two writers, Gita Wolf and Sirish Rao, at an illustrator’s workshop that hosted a group of Gond artists.

Wolf and Rao were so impressed by the energy and originality of his narration that they convinced Shyam to turn it into a book.

He was first excited at the opportunity – “Elwin sahib wrote about my tribe, now it is my turn to write about his!” -, but soon realized the scope of the challenge.

With the help of the two writers, he eventually translated his impressions into a language he mastered: the highly symbolic and bi-dimensional style of Gond painting and their allegories.

In his illustrations, the main elements of his experience translate into beautifully simple, although articulated, metaphors.

The Underground, for instance, is represented by an earthworm, an animal that in Gond traditional beliefs rules the underworld. This latter, in their view, does not belong to humans; in fact, in the London tube, “the busker appeared to be the only human being who was relaxed in the underground, bringing happiness to people with his music – everyone else was trying to move on and get to some place above the ground again”.

Bhajju Shyam photographed by The Times of India

To Shyam, English people come to life at night, and his imagination turns them into Gond bats, flocking to pubs, becoming happier and friendlier – as Pubs seem to set English people free. In his drawings, the pub becomes a Mahua tree, from the flowers of which Gonds make alcohol.

One of the most powerful images of the book is the one representing the merging of Gond time (a rooster) and London time (the Big Ben). The two symbols overlap to depict time as an entity that watches over people. “Symbols are the most important thing in Gond art, and every symbol is a story, standing in for something else”. Shyam points out that this painting was the easiest for him “because it had two perfect symbols coming together”.

Despite its simplicity, “The London Jungle Book” had me thinking a lot. Its almost unintentional, candid anthropology (of travel, of London and of storytelling) resonated with my own journey as an expat in the Netherlands, and the way I approach new places as a traveller.

The way I could relate with the completely new language of this artist from a remote village from the other side of the world reminded me of how stories can bring the most distant people together, when there’s some human truth to them.

My friend Nina is a great storyteller herself. I love her witty sense of humour, her ease of coming up with amusing anecdotes and evoke vivid images of places and things I’ve never seen and make them suddenly familiar.

We couldn’t meet in a jungle, in the hyper-designed, non-random Netherlands (I can’t help thinking that every tree I see here was actually deployed by a landscape architect). We met by chance in a park, though.

We were both taking part in a street dinner where I had brought 5 kilos of homemade tiramisu. The trays became empty in less than 10 minutes, so I spent the rest of the time walking around the other stalls, looking for something yummy and vegetarian. There she was; she had made some South Indian dish, and we started some casual conversation.

We had many more, walking through Amsterdam, although I wish we had more time together.

She can tell a tree from another, knows wild birds by their names, and can bake her own bread. She can come across as worldly as laid back, and take pictures of trees and dogs that are actual portraits.

She made the very far places where she is from feel incredibly close to me, whether she told me about her grandma stitching clothes for all of her grandchildren from one big piece of cloth – which reminded me of The Sound of Music -, or how you can end up having a worship-worthy tree in your backyard without even knowing, or some funny story from her university years. With the same ease she could draw my attention to the political situation in India.

The same day we travelled to Lucca, Nina told me she might move back to India very soon, which she actually did this January.

Over a couple of years, she has become one of my best friends in the world (“in the world” not being a figure of speech, here), and Amsterdam feels very different since she left.

It took me some time to adapt to its new affective landscape, but I started missing my friend in a different way, lately.

Some encounters are true gifts and actually stay with you, some people feel like your neighbours even if they are continents away.

I guess what makes a difference is the way they make you feel about yourself: you feel lucky and talented at the same time for having been able to spot them in a blurred flock of indifferent strangers, players, and uninteresting individuals.

This alone makes you think that the reason you met them is you, with your supposed ability to detect them in the jungle – be it an English, Indian, Italian or Dutch version of it – and connect with their worlds.

[Update – after reading this post, Fiammetta spilled the beans: she still carries a knife. She never got over it, she just dumped Jonathan and moved on to a Swiss guy]

Pingback: Two Indian Recipes - part II: Rasam. - As Soup As Possible

Pingback: Dal makhani - two Indian recipes by Nina Subramani, part I